Submission to the World Medical Association

Public Consultation on a draft devised version of the International Code of Medical Ethics

The Anscombe Bioethics Centre

The Anscombe Bioethics Centre

The Anscombe Bioethics Centre is the oldest national bioethics centre in the United Kingdom, established in 1977 by the Roman Catholic Archbishops of England and Wales. It was originally known as The Linacre Centre for Healthcare Ethics and was situated in London before moving to Oxford. The Centre engages with the moral questions arising in clinical practice and biomedical research. It brings to bear on those questions principles of natural law, virtue ethics, and the teaching of the Catholic Church, and seeks to develop the implications of that teaching for emerging fields of practice. The Centre engages in scholarly dialogue with academics and practitioners of other traditions. It contributes to public policy debates as well as to debates and consultations within the Church.

A key issue: conscientious objection

For the first time this draft Code introduces the idea of “conscientious objection”:

Paragraph 27 reads:

Physicians have an ethical obligation to minimise disruption to patient care. Conscientious objection must only be considered if the individual patient is not discriminated against or disadvantaged, the patient’s health is not endangered, and undelayed continuity of care is ensured through effective and timely referral to another qualified physician.*

* This paragraph will be debated in greater detail at the WMA’s dedicated conference on the subject of conscientious objection in 2021 or 2022. However, comments on this paragraph are also welcome at this time.

Unfortunately, this is deeply problematic as a statement of the rights of conscience in medicine. In the first place it utterly fails to establish the duty of doctors to object to practices and procedures that are unconscionable because harmful, discriminatory, unjust or unethical. The right to conscientious objection is based on the duty to be conscientious which is fundamental to medical ethics. . . continue reading

Comment on the draft International Code of Medical Ethics of the World Medical Association

European Institute of Bioethics

In the context of the International Code of Medical Ethics’ revision, the European Institute of Bioethics (EIB) would like to share some comments with the World Medical Association (WMA) Assembly on paragraph 27 of the draft.

Since 2001, the European Institute of Bioethics has developed an expertise in healthcare ethics, with a special focus on the right of healthcare practitioners to freedom of conscience in their practice.

We acknowledge that the International Code of Medical Ethics (hereafter: the Code) is not a binding instrument for the WMA member states. However, one cannot deny the considerable influence the Code may have on national codes of deontology and even on national laws. Moreover, physicians and healthcare organizations expect from the WMA to promote the highest quality of healthcare relationship between physicians and patients.

Paragraph 27 of the Code is drafted as follows:

Physicians have an ethical obligation to minimise disruption to patient care. Conscientious objection must only be considered if the individual patient is not discriminated against or disadvantaged, the patient’s health is not endangered, and undelayed continuity of care is ensured through effective and timely referral to another qualified physician.

In the following note, we discuss one by one the different parts of this paragraph which we consider, written as such, highly problematic for the physicians’ rights and the patients’ care. . . continue reading

The ethical minefield of COVID-19 vaccination: Informed consent and the obligations of doctors

Australian Broadcasting Corporation

Margaret Somerville

The COVID-19 pandemic has raised a multitude of complex ethical issues — and new ones present themselves daily. These issues, including those related to vaccination, arise at four levels: micro or individual (for example, when a doctor vaccinates a patient); meso or institutional (regarding, for instance, a hospital’s or aged care residence’s policy on vaccinating staff); macro or societal ( a government’s decisions or public health regulations governing distribution of vaccines and access to vaccination); and mega or global (such as a nation’s obligations to provide vaccines to those in developing countries, which are without vaccines).

In many COVID-19 related decision-making situations at each of these levels, decision makers face what is called in bioethics a “world of competing sorrows” — that is, decision making in which there is no “no harm” option, but in which, instead, they must choose to whom harm will be allocated. The ethical difficulties are exacerbated when the harms and benefits do not accrue to the same people or, at least, not in equal measure. A striking example of such a situation at the macro or societal level would be the use of “lockdowns”, when the choice is between protecting public health and inflicting serious economic harm.

What I want to focus on here is a particular micro- level issue: that of a healthcare professional’s obligation to obtain a person’s informed consent to COVID-19 vaccination.

Failure to obtain an informed consent to, or an informed refusal of, medical treatment — which includes vaccination — is medical negligence (medical malpractice). Informed consent to or refusal of medical treatment has three requirements: competence, information, and voluntariness. There is a wealth of research on what is needed to establish each element, but here is a brief summary. . . Continue reading

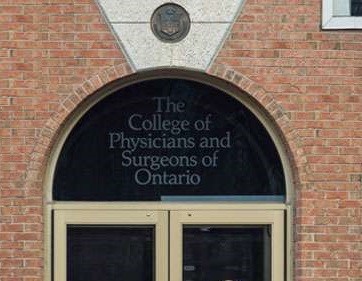

Conscience Project critiques Ontario Physicians College euthanasia/assisted suicide policy

Referral, urgent situations, death certificates, criminal law

News Release

For immediate release

Protection of Conscience Project

Powell River, BC. (28 April, 2021) The 2019 decision of the Ontario Court of Appeal supporting the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario was not the last word on the subject of physician freedom of conscience.

That message was delivered to the College by the Protection of Conscience Project in a submission responding to the College’s request for public feedback on its policy, Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD). The submission focuses primarily on the College demand that physicians unwilling to provide euthanasia or assisted suicide (EAS) for reasons of conscience provide an “effective referral”: that is, connect the patient directly with someone willing to provide a lethal injection or assist with suicide.

The submission on MAiD addresses three points unique to euthanasia and assisted suicide.

Conflicts in urgent situations: If a patient is approved for EAS at some future date, a sudden deterioration of the patient’s condition may cause the patient to ask for immediate relief by EAS. In the absence of an EAS practitioner, other practitioners may be willing to alleviate the patient’s distress by palliative interventions, but not to provide EAS. The Project suggests how this conflict can be avoided.

Falsifying death certificates: Falsification of death certificates is contrary to accepted international standards and can be considered deceptive, unethical or professionally ill-advised. The Project suggests how EAS practitioners unwilling to falsify death certificates can be accommodated by the College and Office of the Chief Coroner even if current government policy does not change.

Criminal law limits on College policy: The Project’s position is that the College cannot proceed against practitioners who, having the opinion that a patient is not eligible for EAS, refuse to do anything that would entail criminal responsibility for homicide/assisted suicide, including “effective referral.” Further, to advise or attempt to coerce them to present EAS as treatment options or to participate by effective referral would seem to be a criminal offence. Finally, since counselling suicide remains a criminal offence, it appears that practitioners cannot be compelled to present assisted suicide or MaiD as treatment options unless a patient has expressed an interest in the services.

The College’s clarification that it does not require objecting practitioners to personally kill their patients is welcome. However, the Project’s position is that this ought to be the norm in a democratic society, not a “concession”or an element in the “accommodation” of freedom of conscience.

While the submission includes specific policy recommendations within the existing MAiD policy framework, it recommends that the College adopt a single protection of conscience policy in line with “the basic theory” of the Canadian Charter of Rights affirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada and consistent with rational moral pluralism. Such a generally applicable policy is included in the simultaneous Project submission to the College on Professional Obligations and Human Rights.

Public consultations on Professional Obligations and Human Rights [Consultation Page] and Medical Assistance in Dying [Consultation Page] are open until 14 May, 2021.

Contact: Sean Murphy,

Administrator, Protection of Conscience Project

protection@consciencelaws.org